Side Quest

Solo exhibition by Elouan Le Bars at the Ygrec Art Centre

Curator: Guillaume Breton

February 6 to April 11, 2026

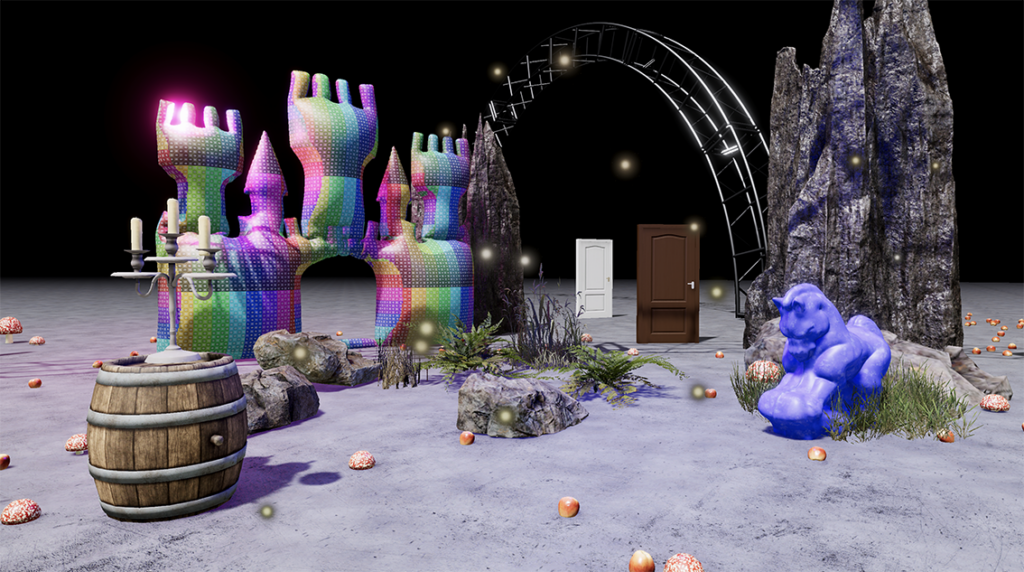

Secondary missions, side quests, games are riddled with them: players can indulge in the leisurely collection of shimmering stars or opt for the systematic smashing of sturdy crates. In the world of video games, this term refers to all the secondary missions which, while they do not directly advance the game’s progress, nevertheless allow for more thorough exploration. By extension, it has come to describe those suspended moments in real-life that are lived like a video game. Life would then be organized by distinguishing two orders of magnitude. First, there would be the main quest, which is imposing and compelling, the pursuit of which requires everyone to be highly performative and competitive at all times. And then there are a multitude of other more fluid moments, which are more conducive to wandering, to drifting, or, more prosaically, to recovering one’s labor power. The porosity between the video game industry and the labor market is at the heart of Elouan Le Bars’ exhibition “Side Quest”. Its title stems from the playable game of the same name which is the main work of the show, and which awaits activation. During the research phase, the artist worked as an anthropologist of immersive cultures, using the approach that he developed for his previous film Corrupted Blood (2024). More specifically, he gathered testimonials from professional gamers, streamers, and coaches through interviews and forums, which were used to write the story of the male protagonist. This is the character we embody in Side Quest, a first-person game designed according to the codes of a “dungeon crawler[1]”, where we push open doors to different spaces, each of which reveals a new part of the story. As it thickens, the narrative structure begins to address the more harmful emotional aspects of competitive gaming: exhaustion, harassment, and the pressure to constantly optimize performance. This is nothing new under the black sun of the burnout society.

The narrator, we learn, will give up on becoming a professional. E-sports, or competitive video gaming, is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity since the turn of the 2010s. As soon as the internet became widespread, it was already common to see how much corporate culture was inspired by the codes of the entertainment industry. The ethnologist Andrew Ross has thus observed, with regard to New Economy companies, that “Those that cannot or do not know how to play will probably end up being left behind [2].” We are equally aware of the subsequent warnings against the pernicious rhetoric of fluidity that is engendered by such a culture [3]. In Elouan Le Bars’ work, however, a new chapter is being written. At present, it is no longer a question of simply importing a ludic logic into the professional sphere, but rather of professionalizing video gaming itself. To put it another way, the commodification of the unproductive time of homo ludens [4] bleeds into the entire social sphere, which now knows neither respite nor downtime.

In Aubervilliers, Side Quest is projected in the center of the space while a scenography composed of doors expands certain symbolic elements of the game. If we were to adopt the perspective of the art world, we could read something else into it. As an artistic medium, video games are little by little gaining recognition as a ‘structure of feeling [5], reflecting an awareness of the present as it emerges at the intersection of emotion and thought. Video games constitute in this way a way of reflecting through action and in the first-person on different individual and collective behaviors in contemporary society. Since any real critical distance or perspective possible, this also ultimately implies moving away from the representative paradigm that we have inherited. When Elouan Le Bars creates a video game to reflect the increasingly close interweaving between play and work, the artist is fully participating in this rapidly evolving aesthetic field. One door leads to the next, and a red space opens onto its counterpart, while our repetitive action on the controller tunes our biorhythms to an infinitely gamified Fordist chain. The grip is total—unless we manage to extricate ourselves from the quests and quit the game.

Ingrid Luquet-Gad

[1] It is a role-playing video game that involves exploring a dungeon full of traps and enemies.

[2] Andrew Ross, No-Collar: The Humane Workplace and Its Hidden Costs (New York, Basic Books, 2003), p. 88.

[3] For example, Tiziana Terranova, “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy”, Social Text, vol. 18 no.2, (2000), pp. 33-38 and McKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto, (Harvard University Press, 2004).

[4] The expression comes from the title of the landmark study on the social function of play. See Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens : a study of the play element in culture, (New York, Roy Publishers, 1950).

[5] Referring to the key concept from the cultural theorist Raymond Williams (1921 – 1988).